Zona Alfa was a game published by Osprey as part of their blue book series way back in January 2020–six whole years ago. It was clearly inspired by games like S.T.A.L.K.E.R. and Metro 2033, which were in turn inspired by the seminal classic: Roadside Picnic. It takes place in a post-apocalyptic Soviet landscape full of mysterious otherworldly creatures, vodka, and unreliable weaponry; that’s really what I’m saying.

And it was pretty darn rad.

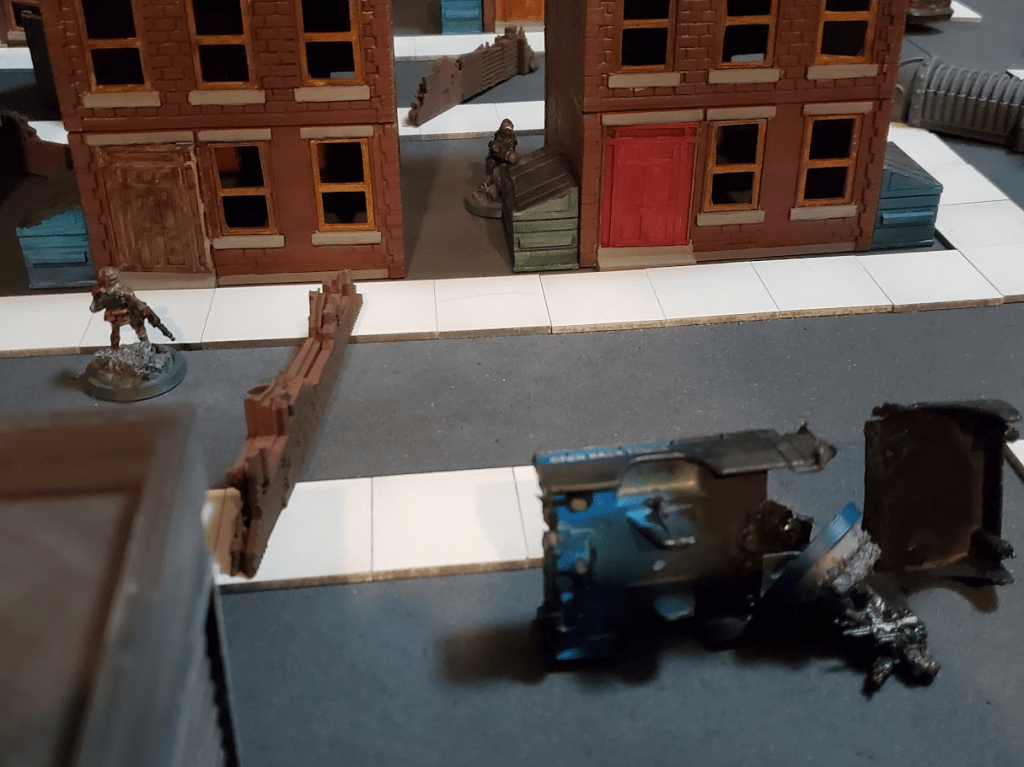

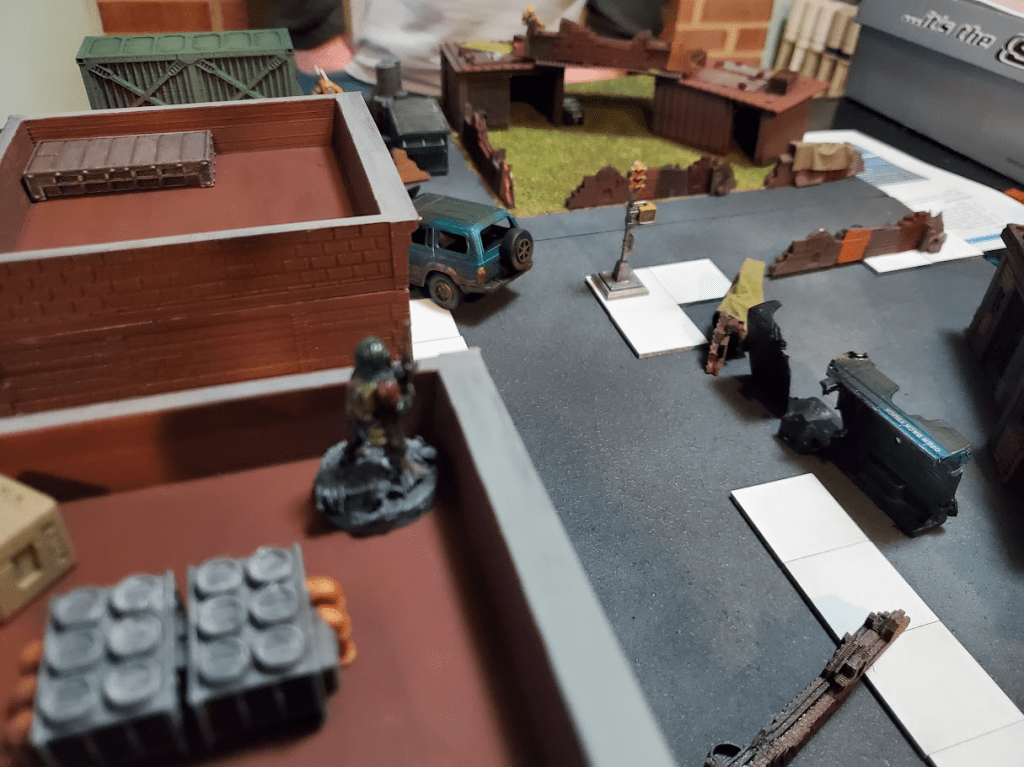

I think about this game more often than almost any other game I played years ago. It comes up all the gosh darn time when I think about my past and future gaming. I played a small campaign around the time of release, in April of 2020 with a good buddy of mine. I painted up two forces, some enemies, and threw down my industrial terrain for a series of matches across a map that escalated the danger level as we went.

I remember a few distinct thoughts about the system after we played it through, and these thoughts are part of why it comes back to mind so often. First off: an important part of the S.T.A.L.K.E.R. video game was encountering anomalies. These were areas where reality might start to bend: the air shimmers, the radiation spikes, and you just know you might make a fortune.

Wait, what?

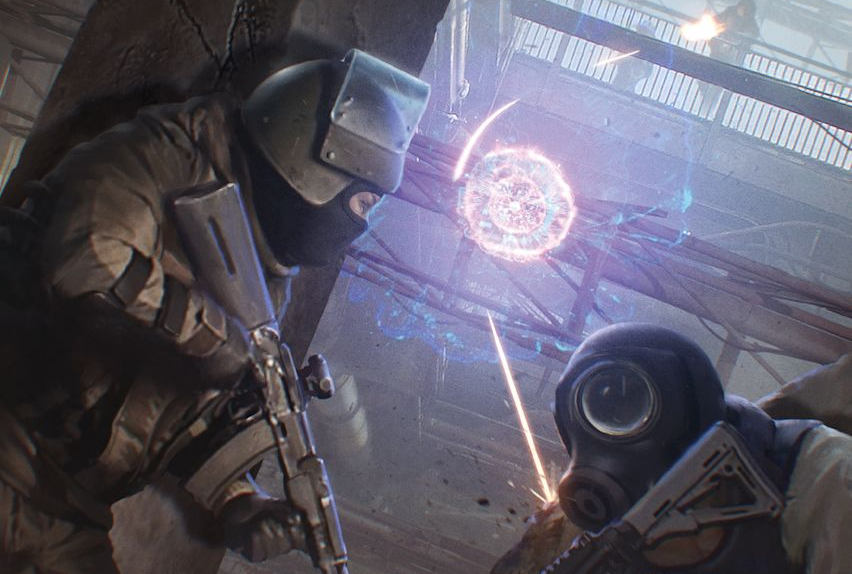

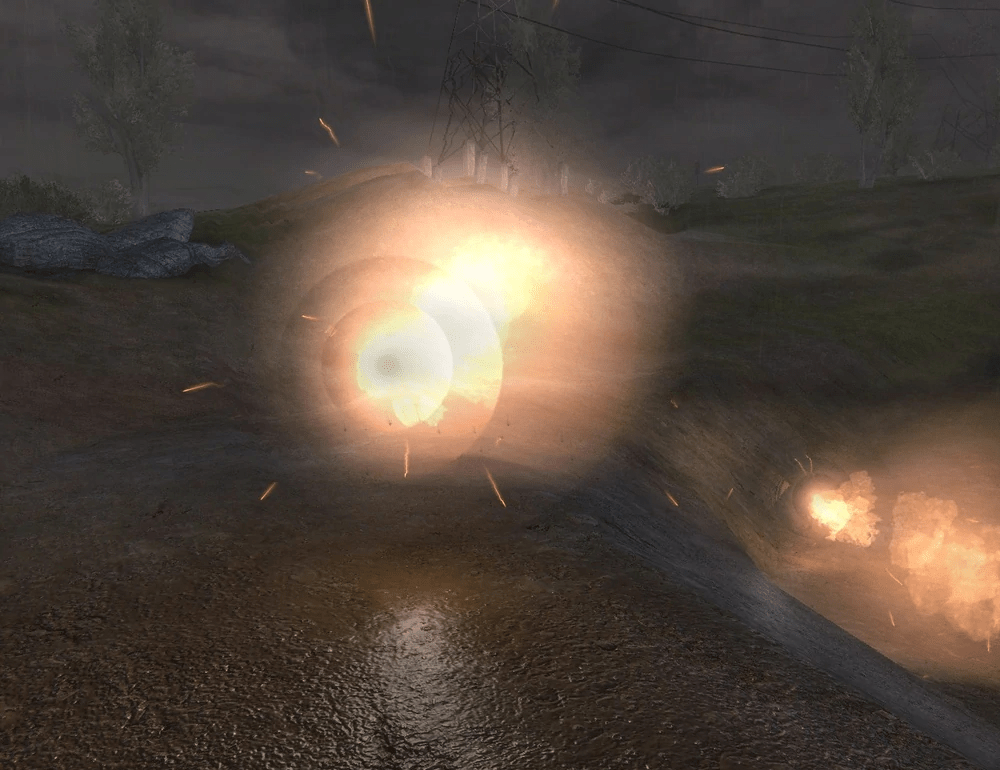

See, there are artifacts in the zone. Strange, inexplicable things that are worth ludicrous amounts of money if you can escape with them. That’s why you’re here: to steal these things, escape, and make enough money to retire young. The catch is that they bend reality. The areas around them become anomalous zones that can do any number of things: slow time, irradiate you, or just reject anything that tries to enter. In the videogame, you take a spare bit of metal–a bolt–and throw it into the anomaly to see what happens. Above, you can see the anomaly partially exploding as the bolt makes contact. It would be a bad idea to advance.

Zona Alfa has a similar idea implemented in it, but without much variety in what happens. I daydreamed of expanding the table of possible events to be something massive, with a variety of potential occurrences, even if they were just narrative pieces. I particularly loved it because it did such a great job of setting a backdrop for the campaign and why you were there. The “Zone” is a dangerous place full of monsters, reality warping artifacts, and the only chance you might ever have of living a good life. So you risk it all, and it often doesn’t pay.

See, one of the themes in the setting is how oppressive the world is. Not only are you contending with crap gear, monsters, and random rocks that might explode your brain: you’re also contending with other people competing to get rich. Sure, they might not always want to kill you–but when the chips are down and a real, collectable artifact is on the line? Watch your back. That’s the basis for the campaign and the game itself. Player vs Player vs Environment (PvPvE). Similar to Frostgrave or other games in the genre, it’s an adventure game where your opponent might kill you or might just race you to collect everything.

The issue? Well, the game is deadly and moves quickly: so the smart player realizes shooting their opponent is the quickest path to a win.

Well, that’s rough. In some ways it fits the setting, but it means our campaign devolved into just killing each other–which was fun in its own way but didn’t quite capture the vibe. So I think about it a lot. I also think about the saving grace: the potential for coop play, which the author absolutely saw and expanded upon.

I never got around to acquiring Kontraband but as I write this post it sits in my cart. I’ve thought about resurrecting this idea and playing a small coop campaign with my son. I recently backed a Kickstarter with some great files for the setting and I’m considering putting together a narrative campaign where we play two parties that have agreed to work together to raid a warehouse for some collection of artifacts. Just a small 5-8 game campaign that will allow me to spend some time painting cool dudes and cooler terrain.

I love the style and vibe. I love the game concept and setting. Something about post-apocalyptic Soviet landscape has always spoken to me, as has the nihilistic and dark science fiction inspired by Roadside Picnic. It’s a fascinating world: oppressive, mysterious, dark, and very brutalist. You oscillate between men sitting around on guitars around a campfire and desperate struggles for survival where your AK-47 jams on you mid-battle and you find yourself crouched behind a car, trying your darndest to unjam it before the enemy gets a bead on you. Then, as you find yourself praying to who the heck knows, a storm comes in out of nowhere, flipping ruined cars and throwing debris. You thank whatever deity that was and run for cover.

That. That’s the feeling I want to evoke–and it’s often a little too random for the precise nature of conflict with another player, so a coop campaign would fit it much better while allowing me to expand the anomalies, the dangers, and randomness that you so often have to deal with in the setting.

Anyway, it’s been snowing and I’ve found myself tapped out on painting motivation since I returned from my work trip, so this is where my wargaming is living. Tune in next time for… uh… probably more Final Girl, because I just beat another Feature Film and want to talk about.

Or, you know, maybe there will be some Russians on my blog. It’s January: the year is young. We’ll see where she takes us.

Leave a reply to platypuskeeper Cancel reply