Time to pull Dragon Rampant 2e off the shelf and give it a read through. This post is NOT meant to be a review, but an overview and first impression based on reading the ruleset. I consider reviews to be weighty things, requiring that I put in my due diligence to play a ruleset enough times to properly judge it. I also avoid reviewing rulesets I only play with my son–which means I’ll likely never write a review for Dragon Rampant 2e.

That said, I think I can lend a reasonable overview that can help guide a purchasing decision for many. Let’s start with my personal bias:

- I very much enjoy both Lion Rampant and Xenos Rampant for what they are: simple fast moving rulesets that portray relatively simple world models.

- I tend toward systems that maintain strong internal cohesion, such that you could almost predict how the next rule will work based on how all the other rules in the system works.

- I love: Chain of Command (1 & 2), Elder Scrolls: Call to Arms, Infinity, and Warhammer 40k 4th Edition.

So I’m predisposed to like this ruleset, is what I’m saying. Let’s jump in.

The Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

It’s still Dragon Rampant, just with more special rules. I mean that. If you enjoyed it before, you’ll enjoy it now. If you disliked it before, you’ll dislike it now. If you specifically disliked it because there were not enough options, you will likely feel a lot better about this edition.

If you’re not familiar, read on for the following sections. This is the shortest BLUF I’ve written to date. If you like the Rampant system, you’ll like this. If you want a streamlined ruleset that is easy to learn and play while letting you put down whatever miniatures you want in a quantity of 20-50 models, you’ll be right at home here.

If you crave complexity, charts, unique interactions, or even truly unique ideas: look elsewhere. This is unabashed beer and pretzels.

Why is the Dragon so Rampant? (What IS this ruleset?)

Dragon Rampant is a ruleset that aims to allow you to play classic fantasy tropes on tabletop with minimal rules overhead. It relies on unit customization through special rules, layered on top of a very simple core ruleset that is easy to learn and play. In a demo, you can learn this game in under five minutes. The real hitch is learning the special rules, but we’ll get to that.

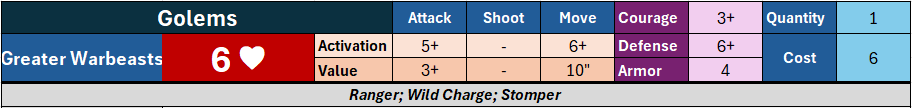

The first hook for the system is the activation mechanics. Let’s look at a unit card I made:

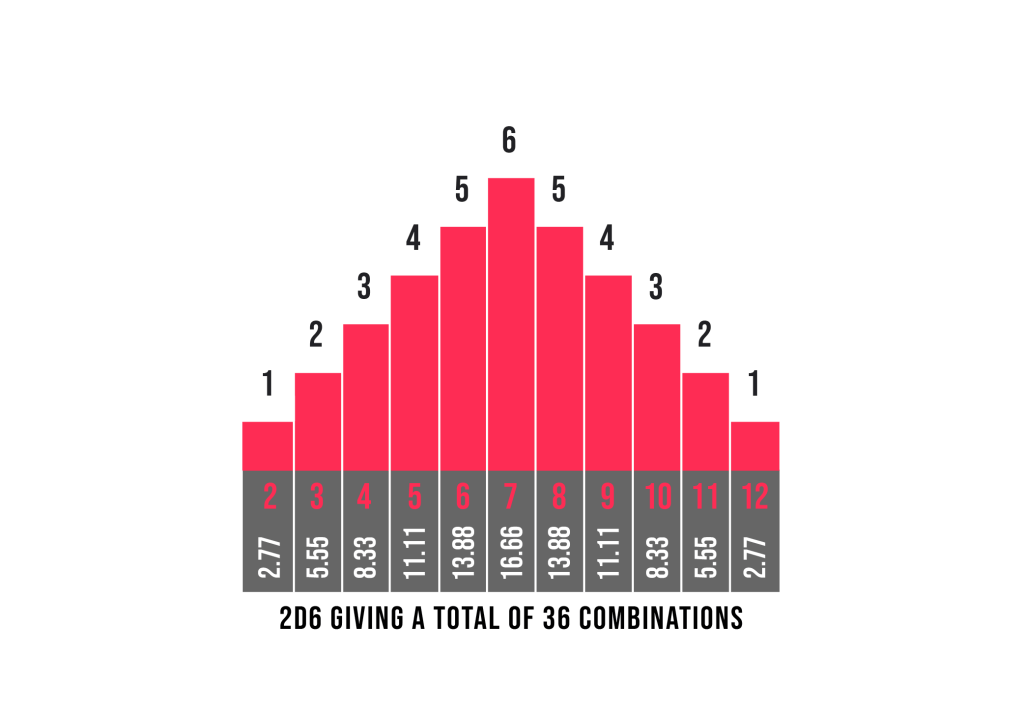

The first thing you should notice is there’s a fair amount of stats (10, in fact, if you include the health value). Specifically, for Attack, Shoot, and Move there is an ‘Activation’ stat. When you take your turn, you roll to activate each unit as you go–when you fail, your turn ends. It’s a 2D6 roll, so you’re dealing with the classic 2D6 bell curve we all know and love:

In practice, looking at the warbeasts above, you can see they want to attack (5+) more than they want to move (6+). Attacking is the command to charge into combat and fight. Movement is just tactical movement around the battlefield. So clearly, these “golems” want to get stuck in more than they want to wander around.

As you play your turn, you’re essentially playing a push-your-luck game of deciding what actions to enact where. You will rarely activate your entire force in one turn, but will instead be forced to focus in on the most important aspects of your battle. You may find yourself more worried with positioning and movement in one turn, while in another you have to emphasize the attack, while in yet another you have to risk movement before a key attack knowing it might end your turn prematurely. It’s a simple but neat system that in the other Rampant games I’ve found quite compelling.

While we’re on the statlines, I’ll note the “Defense” stat. You do not roll defense when attacked–your armor is the number of hits your opponent needs to hurt you. So if you’re armor 3, it takes three successful hits to take away one of your Strength Points. The “Defense” stat is there because all combat is two-way. The attacker rolls their “Attack Value” and the defender rolls their “Defense Value.” These stats represent the number they hit on, so some units are actually better delivering an attack than they are receiving one.

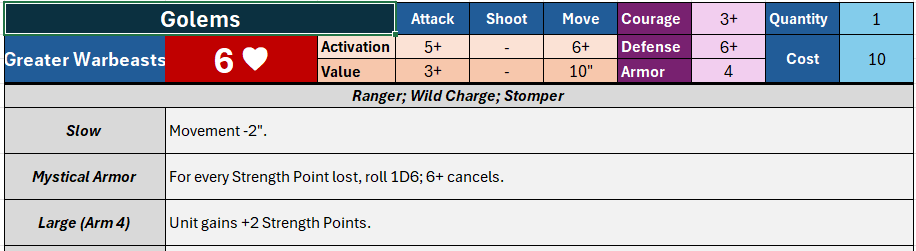

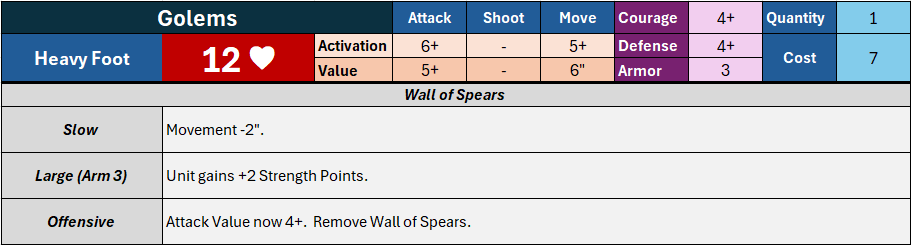

The second major hook is seen here in two images.

The second hook is customization. Here’s two looks at a unit of Golems. In Dragon Rampant, you don’t dig through a million profiles–you build your own off a set of base profiles in the book. This gives you freedom to build as you please. The first unit shown above is a unit of “Warbeasts” that are slow (4″ of movement), but have more health (for 8 total) and better defense (Mystical Armor). In the second profile, I layout a different way of building them as “Heavy Foot”, such that they are still slow, but rather than high armor they have higher strength points (14 total) with worse attack value even with the upgrade. The second unit is cheaper with slightly worse stats and a stronger defensive focus.

For my specific golem models, I am between two choices: a golem without any weapon or a golem with a sword. You can see how I might shape those profiles to fit these two differing golem models.

In either case, the point is that I get to build my army how I want. In fact, either of those units could be any number of models on whatever bases you want, so long as you can track the strength point loss over time. I’m envisioning them as two model units with each model having 7 health (for the total of 14 Strength Points with the ‘Large’ upgrade). You might make it a full unit of 14 golems! You own the freedom to choose here.

That also means your army as a whole is as big as you want it to be. I mapped a dwarf force that is 22 models, but I also mapped a ratkin force that was 50ish. I value this because I want to splash around and paint some dwarves, some elves, and some demons without having to paint full Midgard sized forces. They’re mid-sized projects and a lot more digestible.

The Catch

I’d say the ‘catch’ is the special rules. I made a unit builder because I cannot possibly remember all of the rules. In terms of optional rules, there are 75 total options. The idea that anyone could memorize all of these for such a light ruleset runs in the face of common sense to me–you basically need to write them down.

The rules are so simple that the real burden exists in these special rules. Now, that said, this is not a truly big deal, so long as you can remember them or write them down. As you design your units yourself, that also helps with remembering what their rules are. You’re the one who decided the golem is slow, not some game developer.

I have no other real complaints about the ruleset. That’s not to say it’s perfect–it just has a purpose and executes it well. Whether or not that purpose aligns with you, well…

The Appeal

I’d say the appeal to these rules is obvious: they’re simple, they have just enough interest in the activation system to be fun, and they allow for army customization of relatively small warbands. This is a ruleset you get because you want to paint some cool minis and play something light and breezy with a friend you like chatting with. Or perhaps, like me, you’re playing the rules with your 10 year old and want him to focus on the whimsy and fun of wargames before you crush him with reality in Chain of Command when he turns 13.

Take it from the perspective of “Beer and pretzels classically styled fantasy game meant to be taken lightly.” That’s the appeal in a nutshell.

Other Good Bits

Here I’m just going to say some nice stuff about a ruleset I think is nice:

- The simple magic system is nice and varied without being overbearing.

- The scenarios, as always with Daniel Mersey, are varied and interesting.

- I appreciate the light humor throughout the book.

- There are a ton of alternative rules throughout the book to allow you to customize the game, which is great to see.

- While on the book: it’s well organized, easily read, and flows excellently.

- With a bit of creativity, I have yet to think of any basic fantasy creature I cannot represent.

This next bit requires more explanation: I really like the campaign system. Like with everything in the ruleset, it’s simple and not super in depth, but it works quite well.

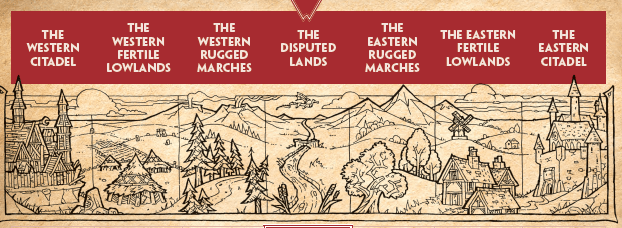

It’s a ladder (or tug-of-war) system where you fight between two sides. Win a battle and you get to select the next one as you close in on your opponent’s home base. If you reach your opponent’s home base and win, you win the whole campaign automatically. Usually, this isn’t a great system: it can stretch forever if you and your opponent manage a 50/50 win/loss ratio. The clever fix is so simple I feel dumb for never having thought of it.

Each battle wins you a form of campaign victory points. Get to a preset amount and you win the campaign. Bam. You are not expected to win three or more battles in a row–but if you do the campaign sucks and you’re glad it’s over. Back to the drawing board.

Instead, by selecting a reasonable VP objective for the campaign, you make sure it’s 5-7 games long and perfectly doable. On top of that, each step on the ladder carries a preset group of missions you roll on so it stays nice and thematic while encouraging you to play across the large variety of scenarios on offer. Near the borderlands you’re likely to fight a brawl or break through effort, but get closer to the citadel and now we’re fighting to assassinate each other’s faction leader. Simple, but effective.

Conclusion

From a read through, again, I can tell you it’s definitely Dragon Rampant. No doubt about it! It’s a lightweight game with a focus on a more traditional fantasy vibe, which does just enough to be interesting and probably worth your while.

It’s not revolutionary or super amazing. It’s not some grand innovation. It doesn’t need to be. This is a game you play to have fun with a friend. It doesn’t always have to be a robust and impressive model of war–sometimes hanging out and rolling dice is all you need.

Leave a comment