My Personal Bias

This review aims to explore Silver Bayonet by Joseph McCullough, outline my opinion of the game, and then highlight what we can learn from the system. Before getting started I think it’s important to understand where I’m coming from. Reviews are inherently opinions so you should know how well my objectives align with your own before you decide how much salt to reach for.

I am a wargamer with years of experience. I wargame professionally. I seek hobbyist wargame rules that do interesting things and portray their own sense of reality (which can be fantastical!) through their rules. I prefer games like Chain of Command over Bolt Action and I prioritize playability through verisimilitude.

I have played around 20 total games of Silver Bayonet, as well as ten or so games of Frostgrave (relevant, I promise). I’ve played both coop and competitive. I ran six game campaign for my club with accelerated leveling which I, quite honestly, did not finish. I could not get myself to write the final mission no matter how hard I tried. I literally did homework instead. To my great shame, I left my final batch of players out to dry. Such was my inability to muster the interest in writing that final mission.

The Bottom line Up Front (BLUF)

I won’t bury the lead here: Silver Bayonet is fine, if uninspired mechanically. This review aims to outline why it is fine and what we can learn from the game. As per my previous reviews, I believe the best rulesets can be boiled down to their objective. They should have a clear concept of what they wish to be.

Unfortunately, when originally writing that I hadn’t considered “What if they wish to be fine?” What do you do when a ruleset only aspires to be an excuse to paint some cool miniatures? Is that ruleset worth your time? Do we factor the miniature painting as part of the value of the rules?

I believe the objective of Silver Bayonet was to write a ruleset with a really cool theme (Napoleonic Gothic Horror) that gives you a reason to paint some cool themed miniatures and roll dice with some friends. Beer and pretzels, have fun, paint some cool minis.

I believe, quite simply, that Silver Bayonet isn’t worth your time as while the theme is absolutely great the execution doesn’t do the theme justice. Let’s go through why.

Silver Bayonet: What is it?

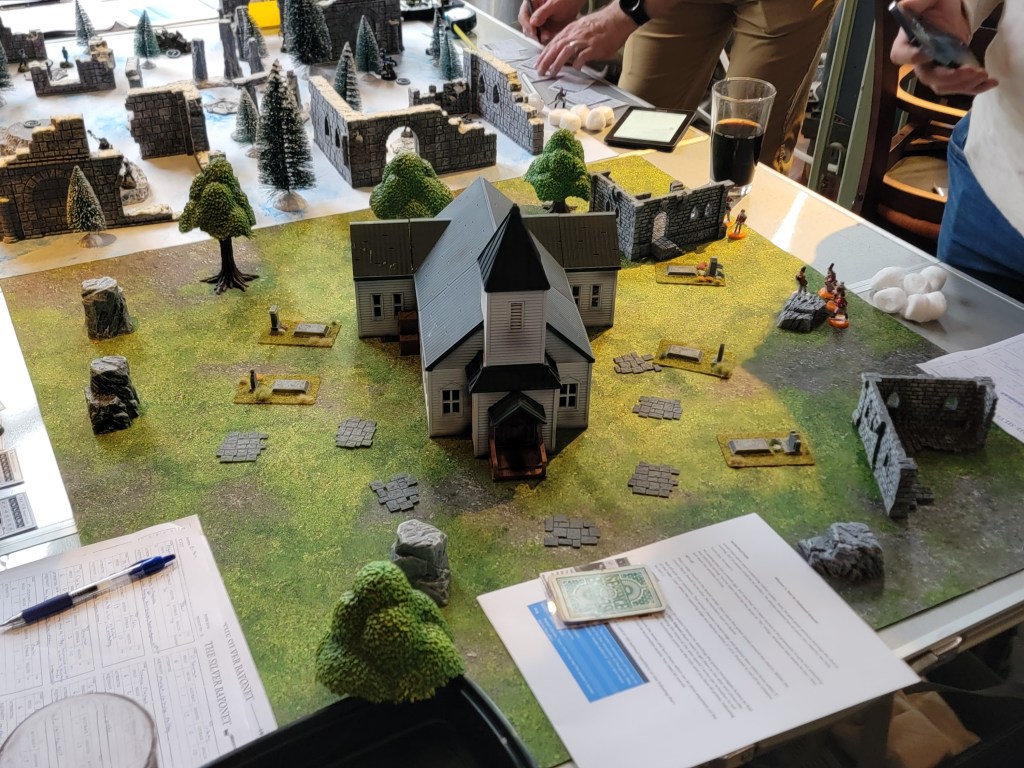

Silver Bayonet is a skirmish sized player versus player versus environment campaign oriented game built on an evolution of the systems used in Frostgrave, Ghost Archipelago, and Stargrave before it. It takes place in the Napoleonic era in a growing list of locales (Iberia, Italy, North America, Egypt, and on and on). Most matches consist of two sides trying to abscond with some valuable treasure while fighting both each other and the monsters spawned by the environment.

You craft a leader for your unit, build out a party, and go adventuring. You level up (mildly), collect loot, and progress through a campaign. There’s a series of campaigns released that are 3-5 games long. There’s also coop campaigns where you and your friend play side by side.

The miniatures are fantastic metal sculpts from North Star Military Figures. They’re some of my favorite sculpts I’ve painted all year an as a quick mini-review: they’re great. If you have a good project, buy them.

The Hook

The hook for this game is the fun theming. When selling my club on playing a campaign I wrote out a little blurb about desperately reloading your pistol as a werewolf bears down on you, forcing you to resort to your silver sword and hope you strike true before he does. I got a lot of interest. Everyone wanted to try the cool alt-historical with vampires, mummies, werewolves, and muskets. I was almost surprised by how much interest I got, with a full 10 players showing up to the initial events!

By the end I still had 5 players, which is actually pretty good retention wise for a campaign. Granted, it was a limited six month campaign. Those still reporting in at the end were enjoying the game and its theme, writing their own stories, and having fun together.

That’s about it. I can’t say anything in the mechanics particularly “Hook” anyone unless you haven’t seen a player versus player versus environment game before. For many people that idea is still novel but honestly it’s been done in many places (and often better) by now.

The Lesson: Verisimilitude Isn’t Just for Analysis

Verisimilitude is the appearance of being true or real. It’s when a ruleset mimics a reality through its elements such that you’ll make decisions that align with reality. When I say “A reality” I mean whatever world the author is trying to create. When you read the lore of Silver Bayonet you get the feel of a world of terror and magic. A world where truly distinct and elite units gather to fight the forces of darkness and alliances are made and broken at will.

Mechanically, the game should back this up. Monsters should be scary, players should have tough decisions about whether to fight their opponents, and your force should be powerful as well as unique. In practice none of these really play out. The game runs on a 2D10 combat system where you roll 2D10 to hit—check against the monster’s armor, and then deal damage with one of those two dice depending on the attack. Some weapons use the power die and others use the skill die. The dice are color coded accordingly. While I praise using 2D10 instead of 1D20 like Frostgrave and Stargrave, the damage you deal is very swingy because it’s based on a single D10. You might deal 1 damage (which is often 0 damage due to monster’s having rules that decrease incoming damage) or you might deal 8 damage, basically wiping out a foe.

The rational choice then becomes to shoot monsters from afar until you roll high. Few of the beasts my players came up against actually gave them trouble once they realized this. So we aren’t very scared.

Now, when you fire at an opposing player, they get the choice to immediately fire back. This means shooting at your opponent is risky—you benefit from firing first but if your shot lands poorly you might find yourself dead. As a result players tend not to engage unless they can do so with overwhelming force. I give credit that I like this aspect of the rules. The responsive fire is a good idea, creating deadly and dangerous combat for both sides. Kudos. My players often decided to align together against the monsters rather than fight each other because they realized that was the easier route to victory. From a campaign perspective this was genuinely good.

As for the forces those players led? They weren’t very unique. There is a huge variety of units to recruit but they generally only differ mildly in stats and abilities. Really, your soldiers just don’t feel very different. This was fine in Frostgrave where your leader was a wizard—your soldiers were fodder, so who cared how unique they were? They were just set dressing. Here, though, your leader isn’t as powerful as a wizard. In fact they’re barely more powerful than the unit they lead. They also don’t have an apprentice like the Frostgrave wizard does, so even less unique characters.

Really, all of our forces felt very similar outside a few stand out unique units, like the werebear or the dhampir. This is a true shame. McCullough paints such a vivid and interesting world but on table it falls very flat, with the 20+ unique soldiers you can recruit all feeling more or less the same. It fails to live up to the reality painted by the lore of the ruleset and that right there is easily the biggest complaint I repeatedly received from my player base.

Here, we see a ruleset that failed to build its reality on tabletop. As a result it feels like a non-entity, missing any real sense of identity and failing to live up to its own world.

Mechanics Without Cause

There’s a few of what I would call “lost mechanics” in this ruleset. Mechanics that don’t really have a purpose or direction. I want to explore on in particular because I think it shows my biggest issue with the ruleset quite clearly. That mechanic is the activation system in the game. The weird problem is first I have to explain the activation of a different game: Frostgrave.

In Frostgrave, you roll off at the start of the turn to activate your forces and flow through the following:

- The Priority player gets to activate their wizard and several models near their wizard. Then the second player gets to do the same.

- The the first player activates their wizard’s apprentice and nearby models, then the second player.

- The monsters activate.

- The first player activates any remaining unactivated models, then the second player.

Now this is interesting. The end result of the system is that your wizard is both the most important model in your party and also works as a leader. The apprentice is clearly the second most important, also operating as a leader. You likely don’t keep them together because that would lead to overlap in your activation bubbles. To have proper control of the field you split them up and let both powerful mages take charge in different places. This works well especially because wizards are interesting. They cast a wide variety of spells that can have dramatic and important effects. They can teleport people across the board, place exploding runes, or summon walls from nowhere to block enemies. They’re rad, is what I’m saying, and the activation system clearly revolves around them because they’re important to the ruleset.

Back to Silver Bayonet. In Silver Bayonet you roll priority and then do the following:

- The priority player gets to activate half their party.

- The monsters get to activate.

- The second player gets to activate their whole party.

- The priority player now activates the remaining half of their party.

This system prioritizes… uh… the monsters, I guess. Which is fine until you shoot them dead just fine. Really, I look at this and think “Well, that made a lot more sense in Frostgrave.” Here, your leader isn’t even important. You activate either half of your party at will. You have no apprentice to speak of, so it didn’t make sense to split the party along lines of leadership. The second player activates their whole party at once, in fact. I’m pretty sure the only reason the first player activates half their party and not all of it is so the second player doesn’t feel like the whole game is activating before them.

The end result is an activation system I still have to look up because it doesn’t reflect anything in its game’s world. It doesn’t show the importance of leadership or tell us anything about how your party operates. It just happens and is maybe a step above full IGOUGO. Maybe. In practice it just feels like a derivative system—which is why I outlined the system from Frostgrave. It’s unguided evolution that fails to really reach a point.

It’s also fine. It works. It’s just a missed opportunity. In fact…

A Missed Opportunity (Conclusion)

That’s the real bottom line. The whole game feels like one giant missed opportunity. It fails to pull together a real sense of its world. It fails to feel like a Napoleonic Gothic Horror. The game plays fine and the miniatures are fantastic but is that really what it takes to eat your time? Try Frostgrave, Elder Scrolls: Call to Arms, MORKBORG, Five Leagues from the Borderlands, or any number of other great games instead.

But if you have to play Silver Bayonet know that you’ll have a decent time. It’ll be fun for the first few games and you’ll have fun painting those miniatures. If you have the terrain already a warband is only around $35. That’s a small investment if you enjoy the painting by itself.

Just know that you probably won’t stick with it. I found extending the game out to six months needlessly painful. I did my best to vary it—I played in every possible setting. Yet fighting from the ruins of Egypt to the frozen cold of Canada just couldn’t do enough to make the game worth playing again.

Silver Bayonet is fine. It’s fine. It’s fine!

I just wish that were praise—because I’d have loved to have a reason to stay in its world and paint more of those beautiful miniatures.

Leave a comment