Here it goes: my first real rules review. We’re starting with the big one, too! Before we start I want to outline for myself and any potential readers what I’m hoping to do here.

My objective is to produce a review that lets you know why a game should interest you and what you can learn from it. I am a firm believer that the best games have clear concepts of what they wish to be. That concept may shift across development, but it should be the heart of what the game will shape into.

Ideally, we can tell what that concept is by reading and playing the game. So what, then, is Chain of Command’s core concept?

It seems pretty clear: it wants to put you in the mindset of a platoon commander in World War 2.

The Bottom Line Up Front (BLUF)

I love Chain of Command. It’s an excellent ruleset and a shining example of what all rulesets should aim for in design: a clear vision closely executed. That doesn’t mean it’s right for everyone, or that every game that achieves this lofty goal is great, but starting off my review series with what I consider to be the best designed ruleset I’ve played just seems right to me. Here’s the bar, let’s see if anyone passes it.

But I’m biased.

Chain of Command has linked me to two of my closest friends. It opened my eyes to truly interesting wargame design. It is, quite honestly, a revolutionary ruleset for me personally. Oh, and it got me a job. I interviewed for my current job by giving a presentation on Chain of Command and blew my interviewers away. I owe this game.

I’d like to think that I couldn’t have analyzed just any game to get this job. Chain of Command is something special, even among the stable of TooFatLardies games. I hope to convey that here.

Chain of Command: what even is it?

This section will explain game mechanics very broadly. Feel free to skip it if you’re already familiar.

Chain of Command is a World War 2 wargame at the platoon scale. This means you’ll primarily have an infantry platoon (30-40 men) and some support (a single tank, an anti-tank gun, an MMG, etc.). The game emphasizes command and control over your forces and has no qualms about friction in its design. It is not a tournament game. It is not perfectly balanced, but it is well balanced.

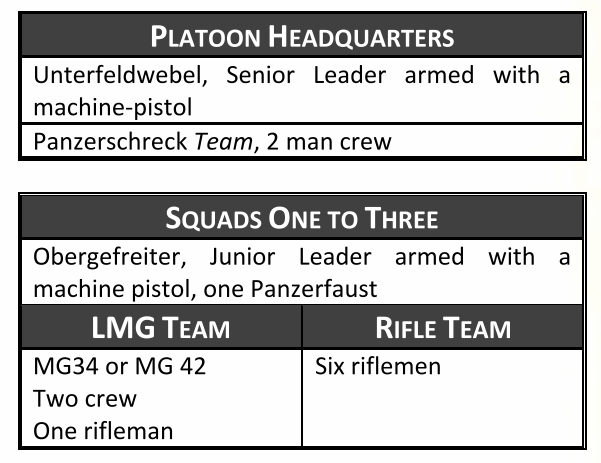

The game is based around historical platoon structures. If you’re playing late war German Heer Infantry, you’ll get the following as your core force:

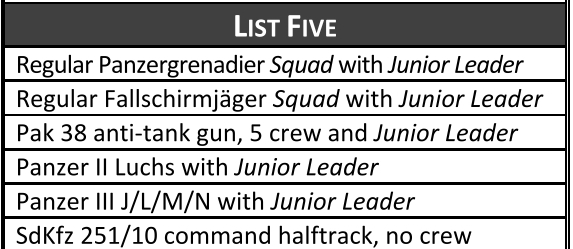

At the start of the game, the scenario will guide you to set “Support Points,” which are spent on supporting elements that can be brought in across the game. For example, if you have 10 support points, you could bring a Pak 38 Anti-Tank Gun and a Panzer III J, per the items on the 5 Point List:

Before putting any forces on the table, you play out the Patrol Phase, where you use markers to imitate the movement of scouting teams ahead of the battle. This will determine the position of your Jump Off Points, which are effectively spawn points for your forces. No troops start on table—they all come on from these Jump Off Points as you play the game.

Every player phase sees you roll dice to determine how much of your force you can control. You proceed to order your men to do the basics: move, fire, go on overwatch, etc. Movement is controlled by dice rolls (Roll 1, 2, or 3D6 and move that many inches), combat is low-lethality when in cover, and special actions like going on overwatch are only possible when commanded via a Junior or Senior Leader.

Leaders are extremely important, as they reduce shock accumulated through combat, allow for special orders, and grant more granular control over your forces.

As you take losses, certain events will be considered Bad Things which cause a roll on the force morale chart. You’ll lose an according amount of Force Morale. Lose enough of your morale and you lose the game. Otherwise, the game ends by accomplishing whatever objective the scenario may set (often times, you’ll set this based on a campaign).

Alright, we have our grounding well enough, let’s get to the good stuff.

The Hook

What mechanics in this game grab me and why?

Strap in. I’m so very sorry. For most games this section won’t be incredibly long, but Chain of Command has so much to talk about, because it teaches us so much about great game design.

We’ll start with force organization. You’re forced to follow the real world platoon structures without a points system allowing for customization. There’s no German platoons fully equipped with Automatic Rifles here (a list I ran in Bolt Action). This forces you to think along the lines of a WW2 Platoon Commander because you’re dealing with the same resources. On top of this, there’s something freeing about not spending a lot of time building out a specific list for your game—just pick your force and play. Further, each platoon has a rating which may grant you or your opponent extra Support Points depending on the difference between your two forces (a balancing mechanism).

Next, we hit the Support Points: your customization. Before your game, you and your opponent determine how many points you’ll have, then secretly select your support options from the list of available choices. These are pointed out as a balancing mechanism. This means you’re never quite sure what your opponent has and you can flex to meet the terrain and scenario at setup.

Then there’s the Patrol Phase: brilliant stuff. You move markers around representing your scouting teams, which lock into place when they come in range of opposing patrol markers. This represents your scouting teams spotting the enemy and reporting back their positions. You use these locked markers to create your Jump Off Points. It’s an entire phase that occurs prior to units hitting the table.

That brings us to Jump of Points. You see, Jump Off Points are where you spawn troops, which means nothing starts on the board. This gives the game an inherent fog of war. You could run up to the building ahead of you, but your scouts spotted Germans there earlier (during the Patrol Phase) and there may be some hiding inside the build (represented by your opponent bringing them onto the field during his/her turn).

Worse yet, it may be a tank that they spent their Support Points on! Once again, we find ourselves thinking like a Platoon Commander who has to consider when he moves his men that they may be going into a trap, or stumble upon the enemy. You have your scout reports to guide you and that’s it.

Then there’s just the general sense of friction to the game. Movement is determined by rolling dice—this caused me to dismiss the game entirely at first glance. Upon playing, I realized it made sense. You have to state out loud what you intend your troops to do. “This section will move to the wall ahead of them, across the road, and take cover.” Then you roll dice. Maybe they roll enough (or over) so they can follow the order, or maybe they roll less. Annoying, right? Well, somewhat. You see, your men got part way there and then noticed something in the woods, which caused them to stop short and try to solve what was going on, or any number of other explanations.

As a Platoon Commander, you have to deal with it.

Same for giving out commands: you roll five dice (usually) at the beginning of the phase and that tells you what you can control. Each number corresponds to a choice: a 2 gives you a section to control, a 3 gives you a Junior Leader (who can order a section) a 6 is a special result that can even earn you a double phase.

Why? Because as a Platoon Commander you’ll never have absolute control. You’ll have to deal with the ebb and flow of battle and put your attention where it will make the most impact.

Okay, okay. This is a lot. One more, I promise: the morale track. Lose a section? Roll for it. You may lose 1 or 2 points of morale. The amount varies, which means you’re never quite sure what disasters will really impact your men and what they’ll be able to grit their teeth through.

There’s yet even more I’m not touching here, honestly, but let’s start piecing these together into my favorite part of gaming.

What Can We Learn?

When I first looked at Chain of Command, I failed to see what made it worthwhile. It just looked frustrating to play. I came around to it and gave it a shot and realized: wow, all of these systems work together! They flow as a cohesive whole to produce a game that really achieves its mission: make you the Platoon Commander.

Let’s examine one choice and how to solve it: moving across an open area to cover. This is a seriously challenging problem that puts most players off the game, leading to many thinking the game is too static, because it’s honestly a hard problem to solve. It is hard to solve, but that’s because it was hard to solve in real life.

Let’s start:

I roll my Command Dice and I have a 3 with which I can command a Junior Leader. I have men who will move from cover, across an open area, to a fence they can use for cover as they move forward. My opponent doesn’t have all of his forces on the board, but he does have a Jump Off Point that I’m angling toward capturing to force a Force Morale Roll on him.

I think about it: if I order my men to move, they may fall short, leaving them in the open without cover if my opponent decides to bring on a section at that Jump Off Point and lay into them. That’s bad—if they break or starting dying off, it may force a morale roll for me, getting me closer to defeat. I can’t just throw my men away on a stupid risk.

Okay, so how can I make it better? Well, thanks to my scouts (the fact that I can see that Jump Off Point) I know where he may have troops. Okay, okay. I got this. I have another Command Dice with a roll of a 3. I’ll order another section to place Covering Fire on the area of that Jump Off Point with their rifle team, and put their LMG on Overwatch so if my opponent spawns I can punish him.

Great! But if he spawns he’ll still shoot first. The Covering Fire will give him -1 to hit, so that helps, but we can make this better. I use my first 3 and have my Junior Leader order the following:

1. Run at the double! Move 3D6 toward that fence. We need to get there before we get shot up!

2. After running, throw a smoke grenade to cover the area in front of us, giving another -1 to hit.

Now if the enemy spawns, he’ll have -2 to hit and firing at me will incur the wrath of my LMG. Far less appealing.

So what just happened?

I had to care about my men dying, so I had to think about how to use the different elements of my platoon to solve the problem. I got lucky—I was able to clearly communicate with both Junior Leaders. If I didn’t have that ability at that moment (by roll two 3’s in my Command Dice) I’d have to come up with a different plan or abandon the idea altogether and work another angle. Right there we had Morale, Jump Off Points, Platoon Structure, and the friction of movement come together to pose a fascinating question. The answer I just gave is historically the answer chosen: lay down covering fire and smoke. Use your Sections such that they work together to solve problems and defeat your enemy.

This is it. This is why I love Chain of Command. Every system informs the same clear vision and works brilliantly together to make you play the period. I’ve had games where we introduced players who were members of our armed forces and were learning on the fly. They quickly realized they could apply real world tactics to achieve victory because that’s how well these systems work together.

Everything you build as a designer should be answering a question. The morale system in Chain of Command exists so that players care about their troops as more than pawns on a board. The friction of movement exists to reinforce the sense of uncertainty behind every order. Everything here exists for a deliberate, thought out reason.

Problems

Alright, okay. It’s not perfect. It has a few serious issues.

For one, the rulebook is a mess. It’s an easy read, but when you sit down to play you realize you don’t… quite know how X works, and finding X is a bear. You grow to accept that you’re just not going to get it perfect and it’ll take a few games. That’s a shame, and I’ll examine a rules writer (Sam Mustafa) who is a shining example of excellent rulebooks and why it matters in another review down the line.

Elites are garbage. They’re a bad system which is fixed in the Blitzkrieg 1940 handbook. You can easily backport the concept, but it’s annoying to have to do so. I’d love an errata that does this for us.

There’s a lack of flexibility inherent to the system. If you want to play a non-standard force, you’ll have to find the COCulator (excellent name; no notes) and stat out that platoon yourself. It’s not hard, but cumbersome and doesn’t come with the rulebook inherently. You have to find it somewhere online. I give credit that most forces already exist for the game, but I do wish the system was in the rules, not just randomly online somewhere (I can’t even tell you where off hand).

Games can run longer than I’d like. The time flies, but I’ve had plenty of games that run 3-4 hours because of how back and forth they can be.

The game really requires you to adjust mindset to enjoy it. You’re not here to play Chess, you’re here to play war. You have to think within the right mindset of problem solving and be willing to stomach the dice or circumstance biting you. They will do so, but in every game I played the better strategy always won. Sometimes, figuring that out meant really thinking it through. For example: I had an opponent lose a game to an improbable event, but he realized that he was trying to control too many units at once and that left his execution somewhat unfocused. I exploited this through admittedly stupid means (see my recent Chain of Command On the Field) and won.

Conclusion

It’s brilliant. It’s a brilliant ruleset. I’m gushing over here. It got me a job. I’m super biased.

That’s why I took so long to explain it. If you’ve read this far, I imagine you’re at least curious or considering giving it a second try. I encourage you to dive in with the right mindset: you may just find your next wargaming love. I’ve spent three years with this game and still feel I have more to discover. I haven’t even tried playing it at 15mm yet, but I will.

Chain of Command is available physically or in PDF from TooFatLardies, but you can also find it more easily shippable Stateside at various website such a Brigade Games ($36 at time of writing). If you’ve read this far into my 2000+ word review, you’ve earned the right to piss that money—just tell your husband/wife the internet man approved the expenditure.

Leave a comment